If you’re struggling with lustful ideas and mental imagery, the most difficult part often isn’t the thoughts themselves. Those intrusive, distracting, explicit thoughts may make you feel bad, but they aren’t really the issue.

It’s the confusion, guilt, and exhaustion that come from trying to stop—and failing—over and over again.

Many Christians dealing with this issue quietly wonder:

Why do these thoughts keep showing up if I’m trying to live faithfully?

Does having the thought itself mean I’ve already sinned?

If I really loved God, wouldn’t this be easier by now?

These questions can turn a momentary mental image into hours—or days—of shame. And when that shame piles up, it often makes the problem worse, not better.

To move forward, it’s important to understand what lustful thoughts actually are, where they come from, and what responsibility you do—and do not—have when they appear.

Why Do Lustful Thoughts Appear?

Human beings are sexual by design. Desire itself is not evil; it is a gift with boundaries. Scripture calls believers to self-control and holiness, not to the erasure of desire altogether.

“It is God’s will that you should be sanctified: that you should avoid sexual immorality; that each of you should learn to control your own body[a] in a way that is holy and honorable, not in passionate lust like the pagans, who do not know God.”

At the same time, we live in a hyper-sexualized culture. Sexual imagery is deliberately used in advertising, entertainment, and social media to capture attention and provoke emotional responses. Your brain notices these cues automatically—often before you consciously register them.

Understanding why lustful thoughts arise can remove much of the unnecessary guilt surrounding them. These thoughts are not only a spiritual issue; they are also shaped by biology, brain chemistry, psychology, and environment.

For men in particular, sexual thoughts tend to appear more frequently on average—not because men are morally weaker, but because male physiology is wired differently.

Biological and Hormonal Influences

One major factor is testosterone. Men generally have significantly higher levels of testosterone than women, and this hormone plays a central role in sexual interest, arousal, and responsiveness.

Testosterone doesn’t create lust on its own, but it increases sensitivity to sexual cues and makes sexual imagery more mentally salient.

Sexual thoughts are also closely tied to the brain’s reward system. Anticipation of sexual pleasure activates dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in motivation, learning, and reinforcement.

Dopamine doesn’t just respond to pleasure—it encourages the brain to repeat whatever behavior or thought pattern led to that pleasure in the past. This is why sexual thoughts can feel intrusive or repetitive, especially if they’ve been paired with strong emotional or physical rewards before.

Other neurochemicals, such as oxytocin, are involved in bonding and emotional attachment. While often associated with intimacy and connection, oxytocin can also strengthen mental associations between sexual imagery and feelings of comfort or relief, making those thoughts more likely to resurface under stress.

Evolutionary and Psychological Factors

From an evolutionary perspective, human brains evolved to prioritize reproduction and survival.

Men, in particular, are wired for strong attentional focus on tasks linked to survival and reproduction. This “one-track” focus—useful for hunting or problem-solving—can also manifest as sudden, intense attention to sexual stimuli.

Men’s focus on sex is likely tied to the fact that most men didn’t reproduce or even had a chance to. In today’s modern society, you might cross paths with 100-200 women a day. And that’s just in person and does not factor in all the interactions on social media and dating sites. Our ancestors were far less densely populated and would not have seen as many non-familial women in their lifetime as the average man sees today. Therefore, he needed to have a certain level of preoccupation with women.

We have evidence that, in ancient human history, only one man reproduced for every 17 women. Sex was a selection pressure, and if you wanted to ensure that your genetic lineage survived, you needed to put a lot of mental and physical energy into sex.

Psychologically, sexual thoughts are easily triggered by sensory input: visual cues, memories, emotional states, or even subtle social signals. These triggers can cause abrupt shifts in attention without conscious intent because the survival of the species depended on it.

Culture, Conditioning, and Individual Differences

Biology alone does not determine sexual thought patterns. Culture plays a powerful role as well. Modern society is highly sexualized, with advertising, entertainment, and social media designed to capture attention by provoking desire. Repeated exposure conditions the brain to associate sexual imagery with stimulation and reward.

At the same time, not all men experience lustful thoughts with the same frequency or intensity. Mood, stress, age, health, personal history, trauma, and emotional well-being all influence how often sexual thoughts appear.

Women also experience sexual thoughts, though patterns and triggers may differ on average. For instance, we know that women prefer to read erotic novels more than watch pornography (Litsou et al., 2024), and women’s sexual fantasies are vastly different from men’s (McCauley & Swann, 1978).

In other words, lustful thoughts are not simply a sign of weak faith or bad character. They are the result of biology interacting with the environment and experience.

What matters most is not that these thoughts arise—but how you respond when they do.

Are Lustful Thoughts Themselves a Sin?

Jesus’ words in Matthew 5:28 are often at the center of this struggle:

“Everyone who looks at a woman with lustful intent has already committed adultery with her in his heart.”

This passage is serious, and it should be taken seriously. But it’s also frequently misunderstood. Well-meaning Christians tend to commit the error of “proof-texting,” in which a passage in the Bible is isolated and taken out of context to make a (usually) self-serving interpretation.

In this case, it must be remembered that Scripture consistently distinguishes between temptation and consent. A thought appearing in your mind is not the same thing as choosing to dwell on it, cultivate it, or act on it. Even Jesus Himself was tempted (Matthew 4:1–11, the story of Jesus being tested in the wilderness), yet remained without sin.

Unwanted sexual thoughts can arise automatically, without intention. That is part of being human.

Having sexual thoughts does not make you a hypocrite, a fake Christian, or someone who secretly wants to sin. It makes you human, living in a body with a nervous system, hormones, memory, and imagination.

The moral issue is not whether a thought appears, but whether you invite it to stay, and if you act on it in any capacity.

Why Trying to “Force Away” Lustful Thoughts Often Makes Them Worse

For many Christians, the instinctive response to a lustful thought is immediate resistance: push it away, rebuke it, shut it down as fast as possible. That reaction makes sense. After all, if lust is wrong, shouldn’t the goal be to eliminate the thought?

The problem is that the human brain doesn’t work that way.

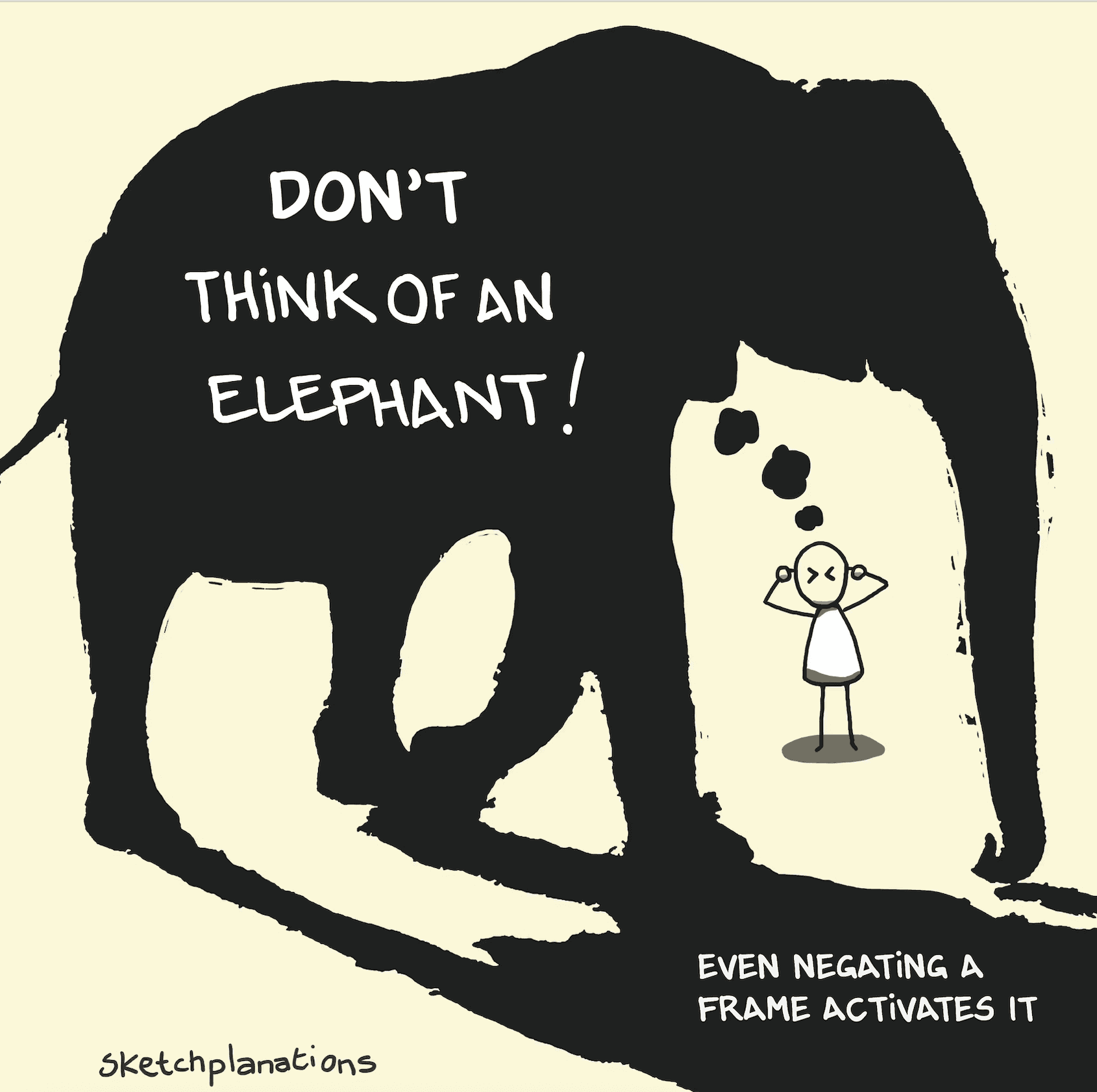

Research in cognitive psychology shows that deliberately trying to suppress an unwanted thought often causes it to return more frequently and with greater intensity. This effect is known as the paradoxical effect of thought suppression.

When people attempt to avoid thinking about something, part of the mind actively monitors whether the forbidden thought is appearing, and in doing so, repeatedly brings it back into awareness (Wegner et al., 1987).

If I tell you not to think about an elephant, the first thing you’re going to do is try not to think about an elephant. This guarantees that you’ll think about an elephant. In practical terms, aggressively fighting a lustful thought can unintentionally keep it alive.

This does not mean self-control is unbiblical or that discipline is pointless. It means that the method matters.

Temptation, Attention, and Moral Responsibility

Scripture consistently treats temptation as something that happens to a person, not something they must immediately feel guilty for. The Bible is also clear that temptations are not sin.

“For we do not have a high priest who is unable to empathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are—yet he did not sin.”

Responsibility begins not at the moment a thought appears, but at the moment of consent and attention.

“But each person is tempted when they are dragged away by their own evil desire and enticed. Then, after desire has conceived, it gives birth to sin; and sin, when it is full-grown, gives birth to death.”

There is a clear progression of events that lead to sin occurring: temptation → attention → consent → sin. This is the same framework upheld by the Catechism of the Catholic Church when deciding whether masturbation is a mortal sin.

A thought that flashes through your mind without invitation is temptation.

A thought you dwell on, replay, or intentionally indulge is something else.

When suppression is your only strategy, the mind often becomes hyper-focused on avoiding failure. That hyper-focus increases anxiety, heightens self-monitoring, and makes sexual imagery more salient.

Over time, this can turn lustful thoughts into an obsession—not because desire is growing stronger, but because attention is being locked onto the problem itself.

This is why many people feel like they are “losing ground” even while trying harder, and why these thoughts never seem to go away.

A More Effective Response To Lustful Thoughts: Notice, Refuse, Redirect

When a lustful thought appears—or any thought you don’t want—the most common reaction is to panic or immediately try to force it away. While this reaction makes sense and is understandable, research shows that this approach usually backfires, often making unwanted thoughts more persistent rather than less.

Psychological studies have repeatedly found that deliberately suppressing unwanted thoughts can cause them to rebound with greater frequency and intensity. This happens because part of the mind begins monitoring for the forbidden thought, unintentionally keeping it active in awareness (Wegner et al., 1987).

Whatever you give energy to grows, including negative thoughts and unwanted behaviors.

A more effective way to deal with intrusive thoughts is to notice the thought calmly, without self-condemnation. This does not mean approving of it or indulging it. It means acknowledging its presence without fear.

Mindfulness-based approaches like this remind us that thoughts do not require action, belief, or emotional engagement. They will go as quickly as they came, as long as you don’t try to force them to leave. Observing a thought without reacting to it is the psychological equivalent of starving a fire for oxygen (Hayes et al., 1999).

Next comes refusal—not through force, but through non-participation. You do not analyze the thought, argue with it, replay it, or shame yourself for having it. You simply refuse to engage with it and play the game of resistance. This interrupts the reinforcement loop that trains the brain to associate sexual thoughts with urgency, relief, or emotional intensity.

Finally, you redirect your attention toward something consistent with your values. This step is crucial. Research on habit formation and relapse prevention shows that urges and cravings tend to rise, peak, and fall when they are not acted upon.

This process, often referred to as urge surfing, teaches the brain that urges are temporary and survivable, weakening their future intensity (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985).

Over time, this pattern retrains both attention and response. Lustful thoughts are no longer rewarded with fear, fixation, or indulgence. Without reinforcement, they lose their staying power.

Self-control is not about never experiencing temptation. It is about learning how to respond wisely when temptation arises—without letting it define your identity, dominate your attention, or dictate your behavior.

How Repeated Responses Shape Habit Loops That Make-Or-Break Lustful Thoughts

One of the most frustrating parts of struggling with lustful thoughts is the sense that nothing is changing, even when you’re trying everything and desperately want things to be different. But lasting change rarely comes from a single moment of resolve. It comes from repeated responses over time.

The more times you do something, the better you get at it—both for better and for worse.

Habits are not driven primarily by motivation or moral intensity, but by loops made up of three parts: a cue, a response, and a reward.

The cue might be a visual trigger, stress, boredom, fatigue, or a familiar emotional state. The response is how you react—internally and externally. The reward is whatever sense of relief, stimulation, or emotional resolution the brain experiences afterward (Wood & Neal, 2007).

Every time a lustful thought appears, your response teaches your brain what to do the next time it shows up. So you must choose the most optimal response, because that’s the response that will become habituated.

Over time, this strengthens the habit—not because desire increases, but because attention and emotion are repeatedly applied to the same pathway.

There’s a saying in neuroscience: “The neurons that fire together wire together.” This phrase captures a basic principle of how the brain learns.

When a particular thought, emotion, and response occur together repeatedly, the neural connections linking them become stronger and faster. The brain begins to treat that pathway as the default option, activating it automatically with less conscious effort (Morris, 1999).

The opposite is also true. When a lustful thought is met with calm awareness, non-engagement, and redirection, the brain receives a different lesson. The thought no longer leads to emotional payoff, urgency, or relief. Over time, the neural pathway associated with that response weakens from disuse, while alternative pathways—those linked to self-control, focus, and value-consistent behavior—become more accessible.

This is why the goal is not to eliminate thoughts by force, but to change the response pattern. The brain does not need perfection to rewire itself; it needs consistency. Each calm refusal is a small signal that teaches the nervous system, “This is not important.” Repeated often enough, that signal reshapes what the brain prioritizes automatically.

In this way, self-control becomes less about constant effort and more about trained instinct. The thought may still appear, but it no longer pulls the same weight—because the brain has learned, through experience, that nothing follows from it.

Consistency matters more than intensity.

Scripture echoes this principle by emphasizing perseverance, renewal of the mind, and steady obedience rather than instant transformation. Growth is not measured by the absence of temptation, but by how consistently you respond when temptation arises.

Over time, the brain adapts to what you practice. Lustful thoughts may still appear, especially under stress or exposure, but they lose urgency. They pass more quickly. They stop dominating attention.

This change doesn’t happen because desire disappears, but because the habit loop has been retrained. And once a loop begins to weaken, freedom becomes less about willpower and more about momentum.

“ Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will.”

What Your Environment And Avoid What Triggers Lustful Thoughts

Even with the right mental response and understanding that you can’t help your biology, it’s important to recognize that your environment matters. Thoughts do not arise in a vacuum. They are often cued by repeated exposure to certain images, contexts, habits, and routines.

While you can’t eliminate every trigger, you can make conscious choices about what you choose to look at and participate in. Just because lustful thoughts are out of your control does not mean you should not remain vigilant about your environment and what you give your attention to.

Jesus didn’t pray for His followers to be taken out of the world, but to be protected within it. The goal is not total control, but wise stewardship.

Or, said differently, there’s a difference between encountering temptation and looking for it.

Repeated exposure to highly sexualized content trains the brain to expect and anticipate sexual stimulation. Each exposure strengthens the association between everyday cues and lustful imagery, making intrusive thoughts more frequent and more vivid. This is not a moral failure; it is how learning works. What you see repeatedly becomes what your mind returns to most easily.

The best move, then, is to reduce avoidable exposure. I can’t control everything that comes across my social media feed, but I can make sure I don’t follow OnlyFans girls.

Scripture reflects this principle when it urges believers to “clothe yourselves with the Lord Jesus Christ, and do not think about how to gratify the desires of the flesh” (Romans 13:14). Notice that the instruction is not to panic about desire, but to avoid provision—the conditions that allow desire to run unchecked.

At the same time, it’s important not to confuse wisdom with hyper-vigilance. Becoming obsessed with scanning your environment for danger can backfire, keeping lustful thoughts at the forefront. Remember: not trying to think about something has the same effect as thinking about it.

The goal is not to live guarded by anxiety, but guided by discernment.

Wise environmental choices don’t make you weak. They make growth easier. And growth, as Scripture and experience both show, is built not on perfection, but on steady, well-supported obedience.

Identity-Based Change: Who You’re Becoming Matters More Than What You’re Fighting

Many people approach lust as a behavior problem: “How do I stop doing this?”

But lasting change rarely comes from fighting what you do. Rather, it comes from changing who you are.

It comes from reshaping identity.

Your brain is constantly updating its sense of who you are based on repeated actions and responses. Over time, the way you respond to temptation becomes part of your self-concept. This is why saying “I’m trying to stop lusting” often feels exhausting, while “This isn’t who I am anymore” creates a different internal posture.

Identity is not just a theological concept—it is a neurological one. The brain is more likely to follow patterns that align with how a person understands themselves. When you repeatedly respond to lustful thoughts with calm refusal and redirection, you are not just weakening a habit loop. You are reinforcing a more profound belief: “I am someone who governs his attention.”

It is easier to act yourself into a new way of thinking than it is to think yourself into a new way of acting.

Scripture reflects this same dynamic. The New Testament consistently frames moral growth not as endless resistance, but as living in alignment with a new identity. Believers are described as people who have “put off the old self” and are being “renewed in the spirit of your minds” (Ephesians 4:22–23). The emphasis is not on constant struggle, but on becoming someone different over time.

This matters because identity-based change reduces internal friction. When your self-image shifts, obedience becomes less about willpower and more about consistency. You stop asking, “Can I resist this right now?” and start acting from the assumption, “This isn’t something I do.”

This does not mean temptation disappears. It means temptation loses its authority.

Lustful thoughts may still appear because you are a human, but they no longer feel like a referendum on your character or faith. They become background noise—noticed, dismissed, and replaced by choices that reflect who you are becoming.

When you consistently respond in ways that align with your values, your brain and your conscience begin to align. This is living with integrity, where your actions, thoughts, and feelings all align.

The struggle becomes quieter—not because desire has vanished, but because your sense of self has stabilized.

Freedom, in the end, is not just the absence of lustful thoughts. It is the confidence that those thoughts no longer define you, direct you, or decide the course of your life.

When It’s Wise to Seek Help—and Why That’s Not Failure

For many people, the approaches described so far—understanding temptation, responding wisely, retraining habit loops, and shaping environment and identity—lead to steady, meaningful progress.

But for some, lustful thoughts don’t just appear occasionally. They become persistent, obsessive, and disruptive, interfering with daily life, relationships, or spiritual peace.

When that happens, it’s important to recognize the difference between normal temptation and a struggle that has become entrenched.

If lustful thoughts dominate your attention, trigger cycles of shame and relapse, or feel compulsive rather than situational, the issue may no longer be something you can—or should—handle entirely on your own.

This isn’t a sign of weak faith or shoddy moral character. It’s a sign that the habit loop has become deeply reinforced and needs additional support to unwind.

Scripture consistently presents wisdom as knowing when to seek counsel rather than relying on isolated effort.

“Plans are established by seeking advice; so if you wage war, obtain guidance.”

Growth does not happen in total isolation.

Support helps for a simple reason: change accelerates in a community. Accountability breaks secrecy. Shared language reduces shame. Structure reduces decision fatigue. And when you’re no longer fighting alone, consistency becomes easier to maintain.

This is where tools like Relay can be helpful.

Relay is designed to support people who want to live in alignment with their values while breaking negative thought and behavior patterns.

Rather than focusing on guilt or fear, it emphasizes awareness, accountability, and steady progress. You’re placed in a group with others who understand the struggle—not to judge, but to reinforce healthier responses and encourage follow-through.

Used properly, a tool like Relay doesn’t replace prayer, discipline, or personal responsibility. It supports them. It provides structure during moments when willpower is low, and reinforcement when old habits try to reassert themselves.

Seeking help does not mean you’ve failed. It often means you’ve reached the point where you’re serious about change.

Growth is rarely a straight line. But when you combine wise internal responses, supportive environments, a stable identity, and the right kind of accountability, momentum builds.

And once momentum takes hold, freedom becomes less about fighting urges and more about living consistently with who you’re becoming.

If lustful thoughts have become more than an occasional temptation—if they’re weighing on your conscience, draining your energy, or pulling you away from the life you want to live—seeking support may be the next wise step forward, not a step backward.

Frequently Asked Questions About Lustful Thoughts

Does having lustful thoughts mean I’m sinning?

No. Scripture distinguishes between temptation and sin. A thought that appears without invitation is temptation, not moral failure. Sin involves consent—choosing to dwell on, cultivate, or act on the thought. Even Jesus experienced temptation without sin (Hebrews 4:15).

Why do lustful thoughts keep coming back even when I’m doing everything right?

Because the brain learns through repetition, not intention. Previous exposure, habit loops, and emotional reinforcement can cause thoughts to resurface automatically. This does not mean you’re failing or regressing. What matters is how consistently you respond—not whether the thought appears.

Is mindfulness unbiblical or spiritually dangerous?

No—when properly understood. Biblical self-control is not about preventing thoughts from appearing, but about governing attention and response. Mindfulness, as used here, simply means noticing a thought without indulging or panicking, then redirecting attention toward what is good. This aligns with Scripture’s emphasis on setting the mind and taking thoughts captive.

“Set your minds on things above, not on earthly things”

“We demolish arguments and every pretension that sets itself up against the knowledge of God, and we take captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ.”

What if lustful thoughts feel obsessive or out of control?

If thoughts become persistent, distressing, or disruptive to daily life, it may be wise to seek additional support. Obsession does not mean moral failure—it often reflects deeply reinforced habit loops that benefit from accountability, structure, or professional guidance. Seeking help is a sign of wisdom, not weakness (Proverbs 20:18).

Will this struggle with lust ever fully go away?

For many people, lustful thoughts become less frequent and less intense over time as responses change and habits weaken. Complete absence of temptation is not the biblical standard. Freedom is measured by stability, clarity, and consistency—not perfection.

References

Cognitive Psychology & Intrusive Thoughts

Wegner, D. M., Schneider, D. J., Carter, S. R., & White, T. L. (1987). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(1), 5–13.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.1.5

Foundational research on intrusive thoughts and why suppression increases thought recurrence.

Habit Formation, Learning, & Neuroplasticity

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychological Review, 114(4), 843–863.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17907866/

Authoritative review explaining cue–response–reward loops and automatic behavior.

Morris, R. G. (1999). D. O. Hebb: The organization of behavior. Brain Research Bulletin, 50(5–6), 437.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-9230(99)00182-3

PMID: 10643472

Peer-reviewed commentary on Hebbian learning (“neurons that fire together wire together”) and neural pathway reinforcement.

Acceptance, Self-Regulation, & Behavioral Change

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press.

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1999-04037-000

Seminal work on mindfulness, non-engagement with intrusive thoughts, and values-based action.

Marlatt, G. A., & Gordon, J. R. (1985). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford Press.

https://www.guilford.com/excerpts/marlatt.pdf?t=1

Introduced “urge surfing” and evidence-based strategies for weakening compulsive response patterns.

Sexual Cognition, Fantasy, & Individual Differences

McCauley, C., & Swann, C. P. (1978). Male–female differences in sexual fantasy. Journal of Research in Personality, 12(1), 76–86.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(78)90085-5

Empirical evidence on sex differences in sexual fantasy content and cognitive patterns.

Litsou, K., Graham, C., & Ingham, R. (2024). Women reporting on their use of pornography: A qualitative study exploring women’s perceived precursors and perceived outcomes. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 50(4), 413–438.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2024.2302375

Recent qualitative research highlighting contextual, emotional, and psychological drivers of sexual behavior.