Chronic masturbation is a persistent pattern of masturbation that feels difficult or impossible to control and continues despite negative consequences or a desire to stop (World Health Organization, 2019).

It does not mean masturbating frequently or having a high libido.

Instead, it is defined by loss of control, ongoing distress, and interference with daily life, not by how often the behavior occurs.

It does not simply mean masturbating often. Rather, the term is used when masturbation becomes compulsive, interferes with daily life, and/or is repeatedly used to cope with stress, anxiety, or emotional discomfort.

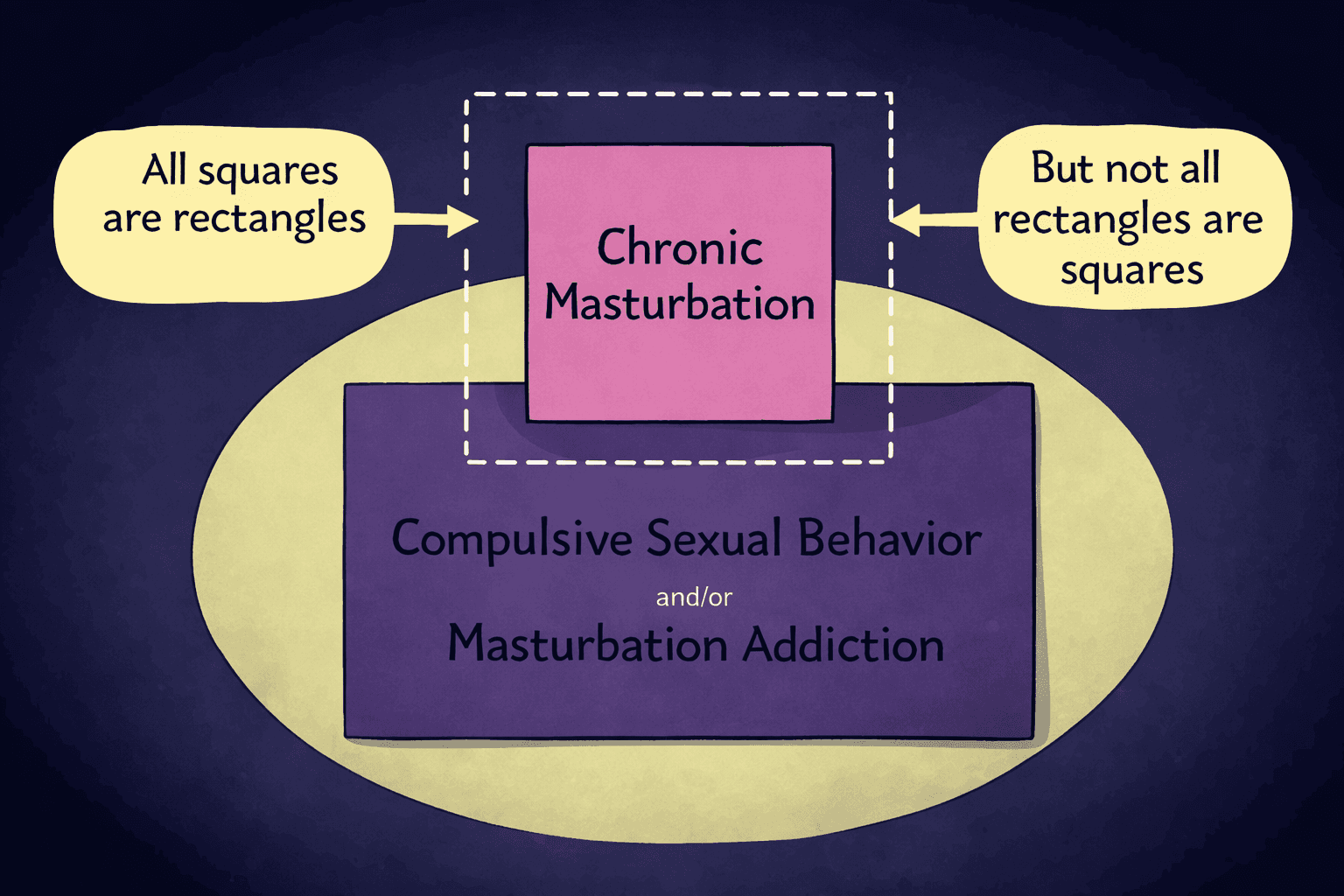

The term often generates confusion, and even controversy, because it is used inconsistently and sometimes inappropriately. Some people use “chronic masturbation” to mean frequent masturbation, while others use it interchangeably with terms like masturbation addiction, compulsive masturbation, or hypersexual behavior.

An idea that has always stuck with me and is perfect for describing situations like this comes from mathematics. All squares are rectangles, but not all rectangles are squares. What this means is that the definition of one object also meets the definition of another, but vice versa isn’t true. In this analogy, chronic masturbation is the square, and all those other terms are the rectangle.

Chronic masturbation shares features with compulsive behavior, addiction, and hypersexuality—but not every case of compulsive masturbation, masturbation addiction, or hypersexual behavior manifests as chronic masturbation.

Mental health professionals also disagree on whether this pattern should be classified as an addiction, a compulsion, or a symptom of an underlying issue, which adds to the confusion.

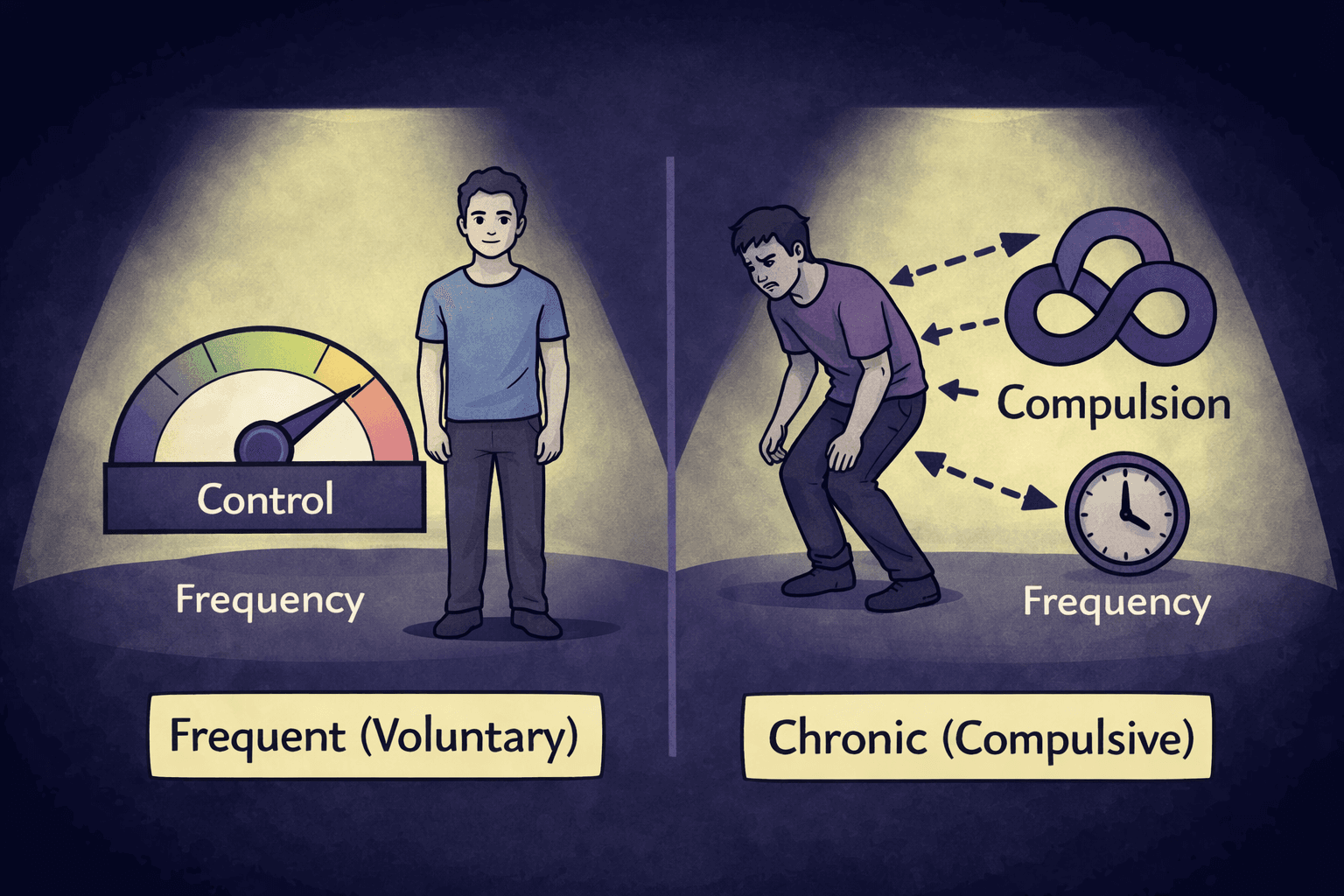

What matters most is not how often someone masturbates, but how much control they have over the behavior and how it affects their life. In that sense, chronic masturbation is defined by loss of agency and impact, not frequency alone.

A person can masturbate frequently without any problems, while someone else may masturbate less often but still feel distressed, out of control, or impaired.

What Does “Chronic” Mean in the Context of Masturbation?

Oxford defines “chronic” as “persisting for a long time or recurring.” In the context of masturbation, “chronic” has taken on a slightly modified meaning.

While it still refers to a persistent, recurring pattern of behavior over a long time period, when paired with “masturbation,” it adds the additional meaning of a behavior that feels difficult or impossible to control, even when a person wants to stop or cut back.

To clarify this, it helps to distinguish between three commonly confused patterns:

Frequent masturbation refers to masturbating often, usually driven by libido, boredom, or opportunity (Herbenick et al. 2010, 2017). There is no inherent distress, loss of control, or negative impact on daily life.

Habitual masturbation involves a learned routine—masturbating at certain times, in certain places, or in response to specific cues. Habits can feel automatic but are still generally flexible and changeable (Lally et al, 2010).

Compulsive masturbation is marked by a strong internal urge to masturbate despite negative consequences, lack of desire, or repeated failed attempts to stop (Gola et al., 2020). This is the pattern most commonly described as chronic.

Time-based definitions, such as masturbating “too many times per day” or “for too many hours,” don’t work because there is no universal threshold for problematic frequency.

One guy might masturbate daily without any problems, while another guy masturbates once a week, but still experiences distress, interference with work or relationships, and a sense of lost control.

For this reason, clinicians and researchers pay less attention to frequency and more to persistence, compulsion, and impact on functioning when describing chronic masturbation.

Chronic Masturbation vs Frequent Masturbation: What’s the Difference?

Although both words are time-descriptive adverbs to modify a sexual action, the difference between the two comes down to control, rather than amount or sex drive.

A guy with a high libido might masturbate often with no problem. Frequent masturbation becomes concerning only when context, control, and consequences either shift or are outright ignored in pursuit of pleasure.

Context matters because masturbation that fits comfortably into someone’s life—without secrecy, urgency, or avoidance—is usually not an issue.

Control matters because chronic masturbation is defined by repeated difficulty stopping or reducing the behavior, even when a person wants to.

Consequences matter because the behavior begins to interfere with sleep, work, relationships, emotional regulation, or personal values.

In other words, frequency only becomes an issue when it is no longer voluntary.

If masturbation feels driven rather than chosen, is used reflexively to manage stress or negative emotions, or continues despite clear negative effects, it may fall into a chronic or compulsive pattern.

Without loss of control or meaningful harm, masturbation—no matter how frequent—does not meet the definition of chronic.

Is Chronic Masturbation the Same as Addiction?

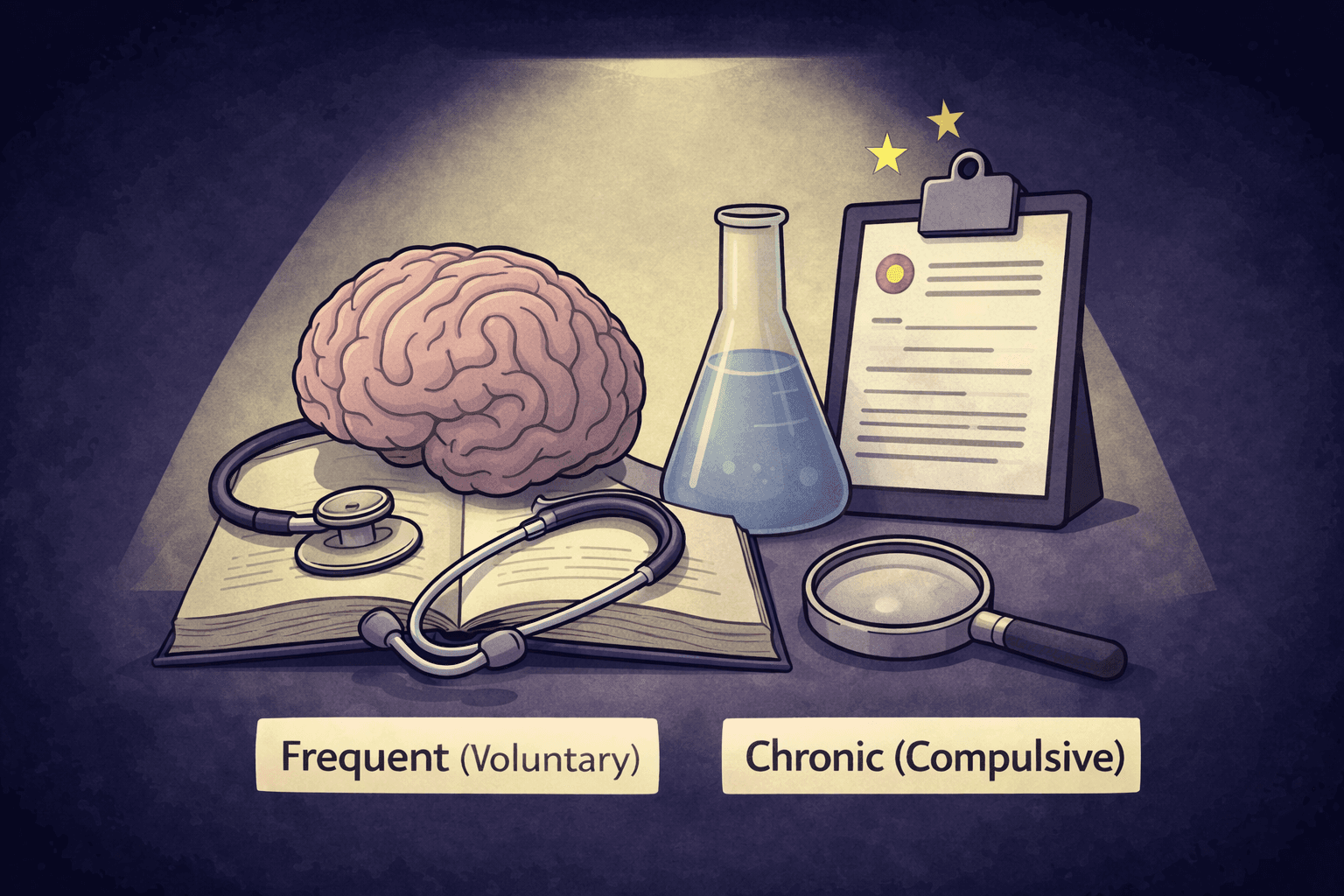

Chronic masturbation is often described as an addiction, but experts disagree on that label. Researchers and clinicians continue to debate whether persistent, difficult-to-control sexual behavior should be understood as an addiction, a compulsive behavior, or an impulse-control disorder.

Marc Potenza, MD, PhD (Yale, addiction psychiatry):

“There is ongoing debate regarding whether compulsive sexual behaviors should be conceptualized as an addiction, an impulse-control disorder, or a manifestation of compulsivity.”

(Potenza et al., 2017)Mateusz Gola, PhD (CSBD lead researcher):

“Although some features resemble addiction, compulsive sexual behavior differs in important ways, including the absence of an exogenous substance and inconsistent neurobiological findings.”

(Gola & Potenza, 2016)Richard Krueger, MD (DSM contributor):

“Hypersexual behavior was not included in DSM-5 due to insufficient empirical evidence supporting its classification as a behavioral addiction.”

(Krueger, 2016)World Health Organization (ICD-11 Working Group):

“Compulsive sexual behavior disorder is not classified as an addictive disorder.”

(World Health Organization, 2019)

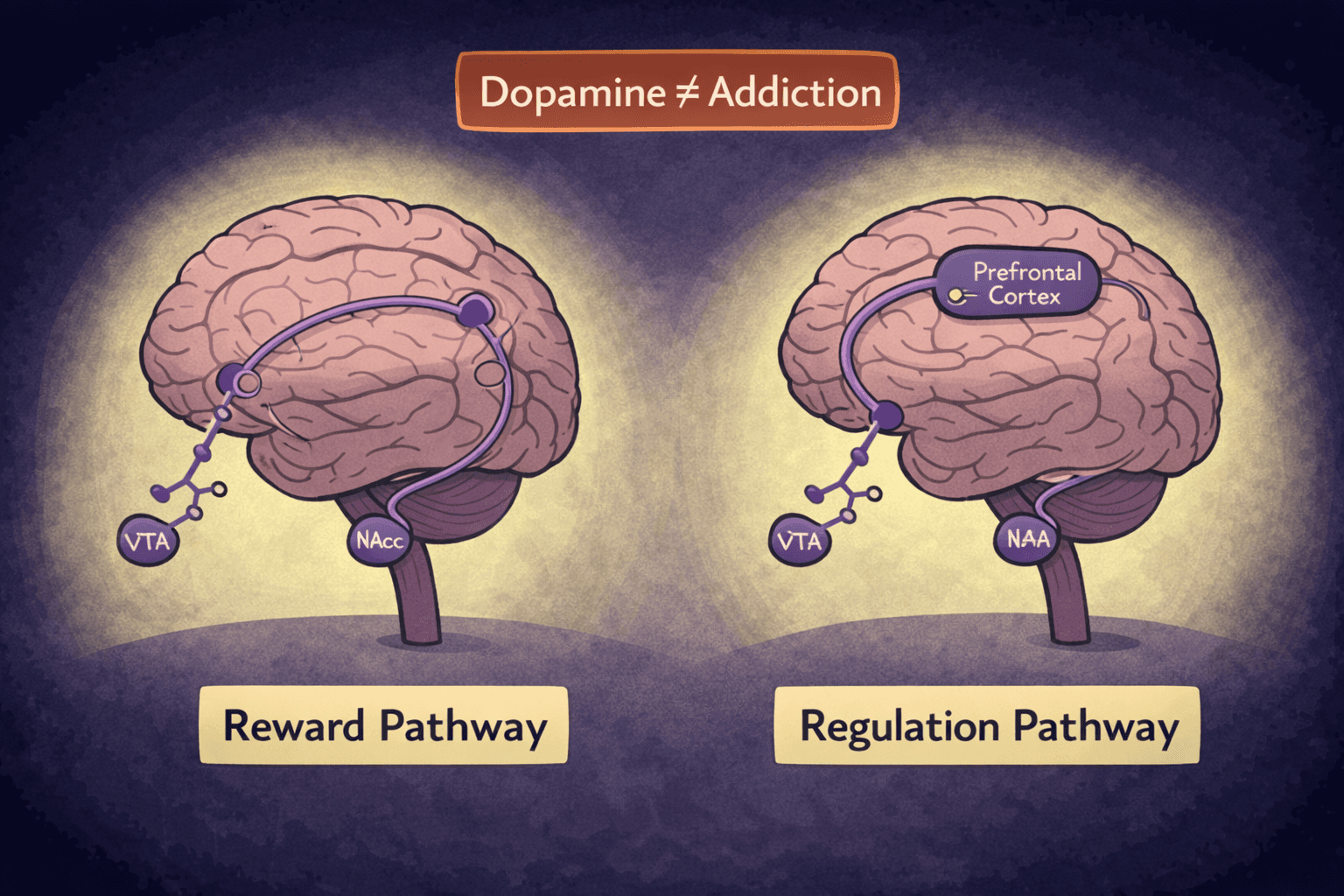

Much of this disagreement stems from the fact that masturbation does not involve an external substance and does not consistently produce the same neurobiological patterns observed in drug or alcohol addiction.

As a result, several diagnostic authorities and leading researchers prefer to describe chronic masturbation as a compulsive behavior rather than a true addiction.

The distinction matters. Addiction typically involves tolerance, withdrawal, and chemical dependence, while compulsion is driven by urges and anxiety relief rather than pleasure alone.

In chronic masturbation, people often report masturbating not because they want to, but because they feel compelled to—sometimes even when they are not aroused. This loss of control aligns more closely with compulsive behavior than with classic substance addiction.

Dopamine is frequently mentioned in discussions about masturbation and addiction, which can add to the confusion. Masturbation activates the brain’s reward system by releasing dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in motivation and reinforcement. However, dopamine release by itself does not equal addiction.

Many everyday activities—such as eating, exercising, or social interaction—also increase dopamine. Problems arise when masturbation becomes the primary or default method for emotional regulation, reinforcing a habit loop that is hard to break.

Because of these nuances, the term “masturbation addiction” remains controversial. It is commonly used in popular culture and recovery communities, but it is not a formal medical diagnosis.

Many professionals instead use terms like compulsive masturbation, compulsive sexual behavior, or out-of-control sexual behavior to describe the same pattern. Regardless of terminology, the core issue is the same: persistent behavior, loss of control, and negative impact on daily life.

Is Chronic Masturbation a Medical or Psychological Disorder?

Chronic masturbation is not recognized as a standalone medical or psychological disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

This often surprises people, especially those who experience real distress or impairment from the behavior. The absence of a formal diagnosis does not mean the problem isn’t real—it means there is no single, universally agreed-upon category specifically for chronic masturbation.

In clinical practice, this pattern is usually understood as part of broader frameworks, most commonly compulsive sexual behavior or hypersexuality. These terms are used to describe repetitive sexual behaviors that feel out of control, persist over time, and interfere with daily functioning. Masturbation can be one expression of these patterns, alongside behaviors such as excessive pornography use or risky sexual activity.

Despite the lack of a standalone diagnosis, clinicians still treat chronic masturbation when it causes distress or dysfunction. Therapists may focus on underlying contributors such as anxiety, depression, trauma, emotional regulation difficulties, or learned coping behaviors.

Diagnosis in practice is therefore based less on labels and more on impact, persistence, and loss of control. The goal is not to pathologize sexual behavior, but to address patterns that are causing harm or preventing someone from living the life they want.

Common Signs of Chronic Masturbation

There is no single test or checklist that can definitively determine whether someone is dealing with chronic masturbation. However, certain patterns tend to show up more consistently when masturbation shifts from a voluntary behavior to a compulsive one.

Experiencing one or two of these signs does not automatically indicate a problem, but persistent combinations of them may be worth paying attention to.

Common signs may include:

Loss of control, such as feeling unable to stop or cut back despite wanting to

Using masturbation to cope with emotions like stress, anxiety, loneliness, boredom, or sadness

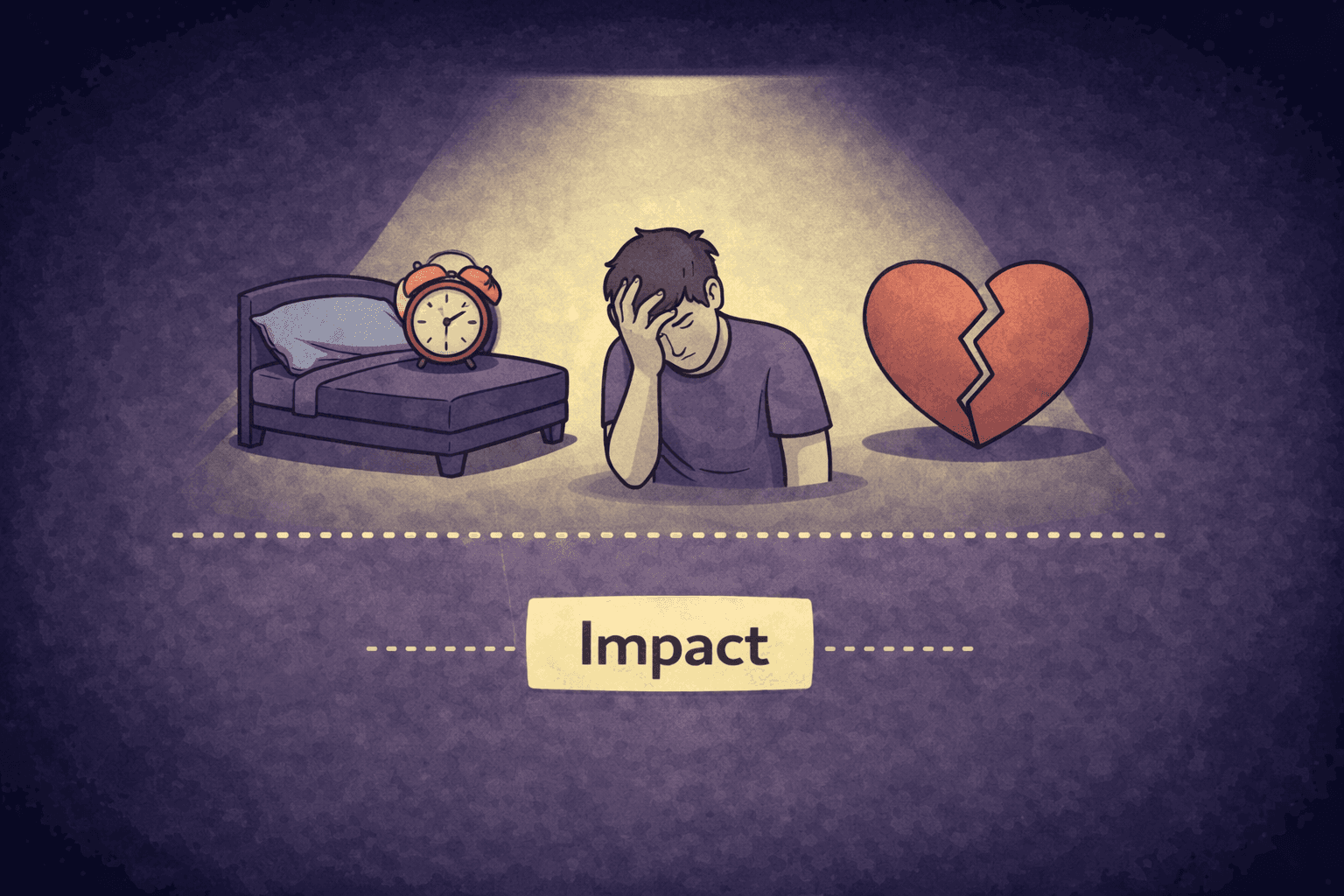

Interference with daily life, including work, school, relationships, sleep, or responsibilities

Masturbating without desire or arousal, driven more by urge or habit than genuine sexual interest

Repeated failed attempts to stop or reduce the behavior, often followed by frustration or guilt

These signs focus less on how often masturbation occurs and more on how it functions in someone’s life. Chronic masturbation is characterized by distress, persistence, and disruption—not by occasional urges or periods of increased sexual activity.

Why Some People Develop Chronic Masturbation Patterns

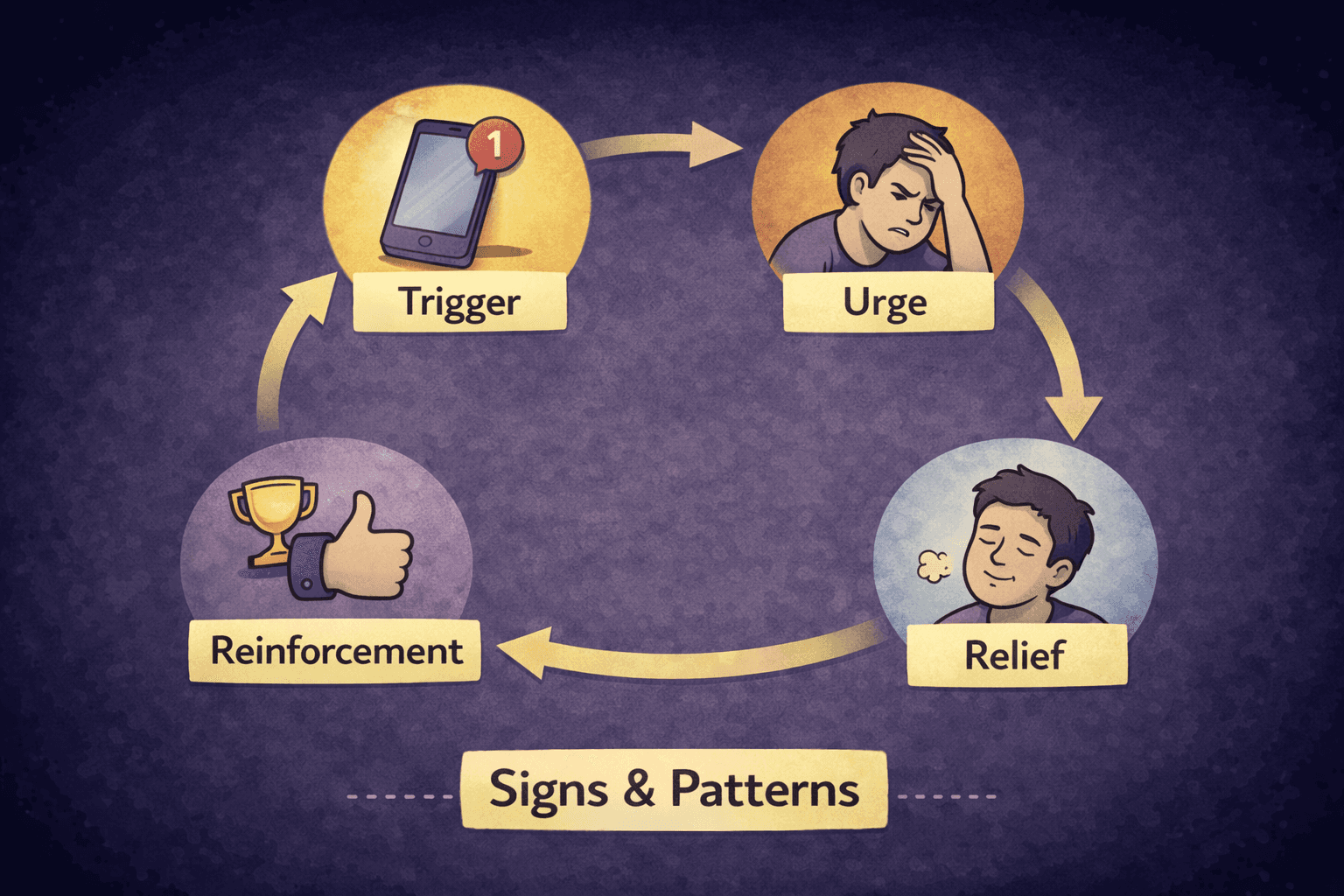

Chronic masturbation rarely develops in a vacuum. For many people, it becomes a learned coping strategy that temporarily relieves discomfort but is difficult to stop over time. Masturbation is a fast, reliable way to change how someone feels, which makes it especially appealing during periods of stress or emotional overload. When it consistently reduces tension or distracts from discomfort, the brain learns to reach for it automatically.

Emotional factors often play a central role. Anxiety, depression, and social isolation can increase reliance on masturbation as a way to self-soothe or escape. In these states, motivation is low, and discomfort is high, making immediate relief more attractive than long-term solutions.

Over time, this can create a pattern where masturbation becomes the default response to negative emotions rather than a conscious choice.

For some individuals, trauma and avoidance are key contributors. Masturbation can serve as a way to disconnect from painful thoughts, memories, or feelings without directly confronting them. Like other compulsive behaviors, it offers short-term relief while reinforcing avoidance, which can deepen the cycle rather than resolve the underlying issue.

Neurobiology also plays a role. Masturbation activates dopamine pathways involved in motivation and habit formation. When the behavior is repeated in response to specific emotional or environmental triggers, habit loops can form: trigger, urge, behavior, relief. Over time, the brain begins to associate masturbation with regulation rather than pleasure alone, making the behavior feel automatic and hard to interrupt.

Pornography can accelerate this process, but it is not a requirement for chronic masturbation to develop. Porn provides novelty and heightened stimulation, which can strengthen habit loops and increase compulsive use for some people.

However, many individuals experience chronic masturbation patterns without heavy or any porn use at all. The common thread is not porn itself, but repeated reliance on masturbation as an emotional regulator.

Is Chronic Masturbation Harmful?

Chronic masturbation is not inherently harmful in the way a toxin or disease is, but it can become problematic when it consistently interferes with mental health, relationships, or daily functioning.

The impact depends less on the behavior itself and more on how it is used, how often it overrides choice, and what it replaces in a person’s life.

From a psychological standpoint, chronic masturbation is often associated with increased distress rather than relief over time. While it may temporarily reduce anxiety or tension, relying on it as a primary coping mechanism can prevent someone from developing healthier ways to manage emotions. This can contribute to cycles of guilt, frustration, low motivation, and a sense of being “stuck,” especially when repeated attempts to change the behavior fail.

The social and relational effects can be significant as well. Some people find that chronic masturbation leads to withdrawal, secrecy, or reduced interest in real-world intimacy.

It may interfere with romantic relationships, create tension around trust or availability, or crowd out social connections by becoming a private escape from discomfort rather than a shared experience with others.

Physical issues are less common but can occur in extreme cases. These may include genital irritation, soreness, or injury when masturbation is excessive or compulsive over long periods. Importantly, physical harm is not the defining feature of chronic masturbation and is rarely the primary concern; psychological and functional impacts tend to appear first.

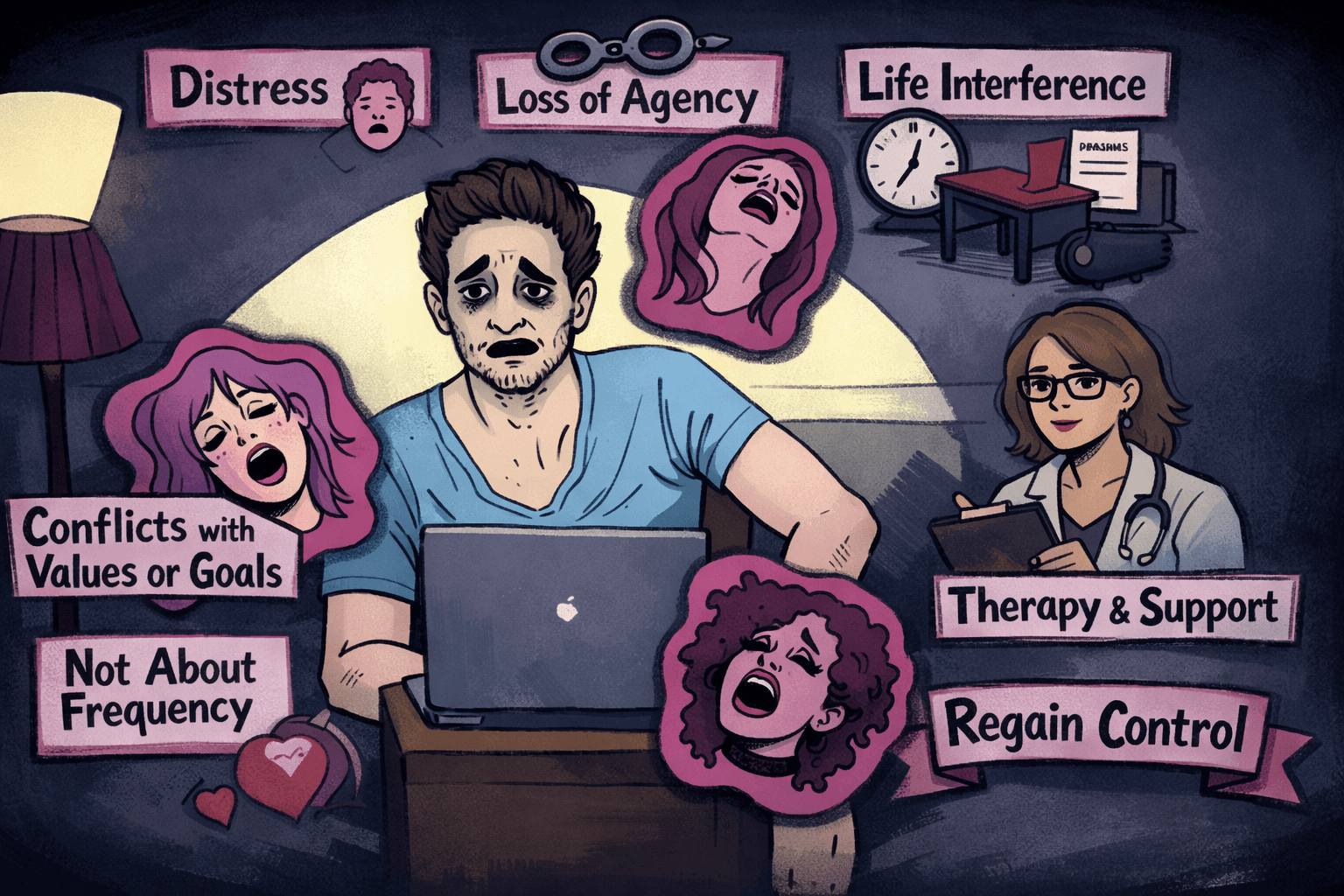

When Does Masturbation Become a Problem?

Masturbation becomes a problem not when it happens often, but when it creates ongoing distress, loss of control, or meaningful interference with life. Frequency alone is a poor indicator. The more important question is whether the behavior feels chosen—or driven.

Distress. If masturbation leaves you feeling anxious, frustrated, ashamed, or emotionally depleted on a regular basis, it may no longer be serving a healthy role. Occasional regret is common with many habits, but persistent emotional discomfort suggests a deeper issue that deserves attention.

Loss of agency. When someone repeatedly tries to stop or cut back and finds themselves unable to follow through, masturbation may be functioning compulsively rather than voluntarily. The behavior can begin to feel automatic, urgent, or disconnected from desire, which often leads to a sense of helplessness or resignation.

Value and goal conflict. This might include undermining efforts to improve mental health, build relationships, increase focus, or live in alignment with deeply held beliefs. Even if the behavior causes no obvious external harm, internal conflict alone can be a meaningful form of suffering.

Life interference. When masturbation regularly disrupts sleep, work, relationships, social engagement, or responsibilities, it signals that the behavior is taking priority over important areas of life. At that point, the issue is not sex or desire—it is the loss of balance and control.

What to Do If You Think You Struggle With Chronic Masturbation

If you recognize some of the patterns described above, don’t panic or self-diagnose. Instead:

Regain agency and reduce distress. Change usually happens through a combination of awareness, behavioral shifts, and support, rather than sheer willpower alone.

I put these solutions together because they often go together. When you focus on the things that are within your control, you lower your stress levels. With lower stress levels and a sense of control, you may find that you are less inclined to masturbate because you are no longer seeking relief from distress.Start with self-reflection and awareness. Pay attention to when and why the urge shows up. Is it tied to stress, boredom, loneliness, anxiety, or avoidance? Identifying triggers increases awareness of internal cues and creates distance between stimulus and response, making automatic behavior easier to interrupt (Wood & Neal, 2007).

Research shows that observing urges without immediately acting on them weakens habitual responding and restores self-regulatory control (Bowen & Marlatt, 2009; Baumeister & Vohs, 2007). This process also helps separate urges from identity by reframing them as transient mental events rather than commands that must be obeyed (Teasdale et al., 2002; Hölzel et al., 2011).Replace the habit, not just the behavior. Trying to simply “stop” often backfires. Masturbation functions as a physical and emotional regulator, reliably altering dopamine, stress, and arousal systems in the brain (Georgiadis & Kringelbach, 2012). Suppressing the behavior without replacing its regulatory function can increase craving by keeping the urge neurologically powerful (Wegner, 1994).

Neuroscience suggests that a more effective approach is to replace the old habit with a new one. For example, engaging in activities such as exercise, walking, or writing can shift arousal and mood through overlapping neurochemical pathways, without reinforcing the same stimulus–response loop (Berridge & Robinson, 2016; Lynch et al., 2013).Use accountability and structure. Many people struggle in isolation but improve quickly with light accountability. This can be a trusted friend, a group, or a structured habit-change system.

Tools like Relay App are designed specifically for this purpose—helping you track patterns, build streaks, and stay accountable in a group of like-minded men who are all facing the same challenges. This type of accountability and camaraderie supports behavior change daily, motivating you to stay consistent when you face a challenge.Consider therapy or counseling. If chronic masturbation is tied to anxiety, depression, trauma, or emotional dysregulation, working with a therapist can be extremely effective. Therapy focuses less on the behavior itself and more on the underlying drivers, helping you build healthier coping strategies and regain a sense of control.

Know when to seek professional help. If the behavior feels completely unmanageable, causes significant distress, or interferes with work, relationships, or mental health, it’s a good idea to seek professional support sooner rather than later. Chronic masturbation is often a signal, not the root problem, and addressing what’s underneath can make change feel far more achievable.

Key Takeaways

Chronic masturbation is not the same as frequent masturbation. It refers to a persistent, difficult-to-control pattern, not how often the behavior occurs.

The core issue is control and impact, not libido or desire. Distress, loss of agency, and life interference matter more than frequency.

Chronic masturbation is not a formal medical diagnosis, but it is commonly addressed within frameworks like compulsive sexual behavior or hypersexuality when it causes harm.

Support and practical tools are available, including habit-change strategies, accountability systems, and professional counseling.

Change is possible. With understanding, structure, and the right kind of support, many people can regain control and reduce compulsive patterns over time.

The most important thing to remember is this: struggling does not mean you are broken.

With the right combination of awareness, structure, and support, it is entirely possible to reduce compulsive patterns and build a healthier relationship with your behavior—and with yourself.

References

References

Diagnostic Frameworks & Clinical Classification

World Health Organization. (2019). ICD-11 for mortality and morbidity statistics: Compulsive sexual behavior disorder.

https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1630268048

Krueger, R. B. (2016). Diagnosis of hypersexual or compulsive sexual behavior can be made using ICD-10 and DSM-5 despite rejection of this diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association. Addiction, 111(12), 2110–2111.

https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13366

PMID: 27086656

Reid, R. C. (2016). Additional challenges and issues in classifying compulsive sexual behavior as an addiction. Addiction, 111(12), 2111–2113.

https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13370

PMID: 27098081

Addiction vs. Compulsion Debate

Potenza, M. N., Gola, M., Voon, V., Kor, A., & Kraus, S. W. (2017). Is excessive sexual behaviour an addictive disorder? The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(9), 663–664.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30316-4

Kraus, S. W., Voon, V., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction? Addiction, 111(12), 2097–2106.

https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13297

Sexual Behavior Prevalence & Normative Data

Herbenick, D., Schick, V., Reece, M., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2017). Sexual behaviors, relationships, and perceived health status among adult men and women in the United States: Results from a nationally representative probability sample. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(2), 200–210.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.12.004

PMID: 28143730

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Neuroscience of Sexual Reward & Regulation

Georgiadis, J. R., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2012). The human sexual response cycle: Brain imaging evidence linking sex to other pleasures. Progress in Neurobiology, 98(1), 49–81.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.05.004

Berridge, K. C., & Robinson, T. E. (2016). Liking, wanting, and the incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. American Psychologist, 71(8), 670–679.

https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000059

Habit Formation, Self-Regulation, and Behavioral Control

Lally, P., van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998–1009.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit–goal interface. Psychological Review, 114(4), 843–863.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.843

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2007). Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 115–128.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00001.x

Wegner, D. M. (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review, 101(1), 34–52.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.1.34

Mindfulness, Metacognition, and Urge Interruption

Bowen, S., & Marlatt, G. A. (2009). Surfing the urge: Brief mindfulness-based intervention for college student smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(4), 666–671.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017127

Teasdale, J. D., Moore, R. G., Hayhurst, H., Pope, M., Williams, S., & Segal, Z. V. (2002). Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 275–287.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.70.2.275

PMID: 11952186

Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671

Behavioral Replacement & Exercise

Lynch, W. J., Peterson, A. B., Sanchez, V., Abel, J., & Smith, M. A. (2013). Exercise as a novel treatment for drug addiction: A neurobiological and stage-dependent hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1622–1644.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.011